The elusive history and politics of Pakistan’s truck art

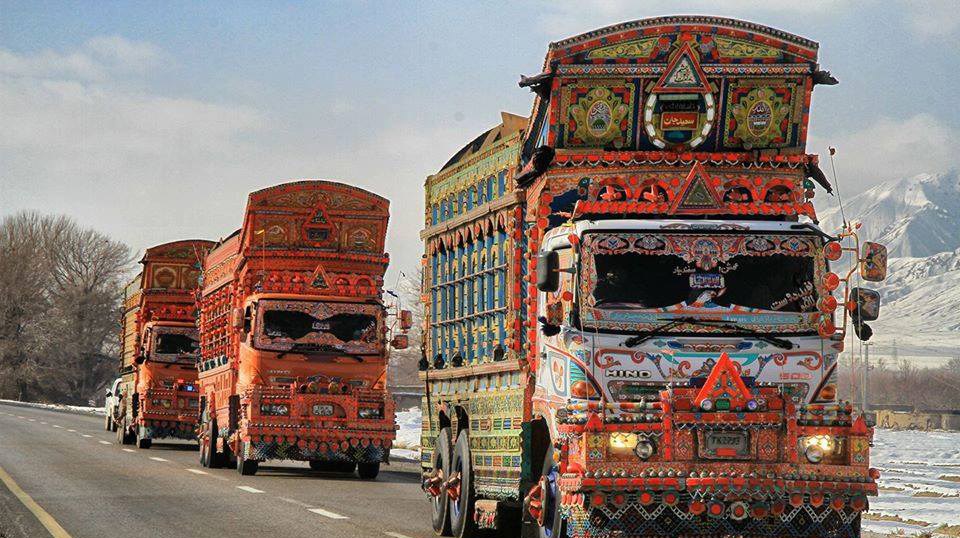

Pakistan’s ‘truck art’ is now quite a well-known ‘genre’ around the world. For long, it has been an homegrown art-form in South Asia, especially in Pakistan, where the whole idea of decorating trucks (also, lorries and even rickshaws) with complex floral patterns and poetic calligraphy, has evolved in the most radiant and innovative manner.

This indigenous art-form became known to the developed world from the 1970s onwards when European and American tourists took back the photographs they had taken of heavily painted and decorated trucks and buses on the roads and streets of Pakistan.

From the late 1980s, the government of Pakistan and enterprising individuals began to organise truck art exhibitions abroad and by the early 2000s, the genre had established itself as an exciting and vibrant ‘folk art-form’ from Pakistan.

So much has already been written and said about truck art. Yet, very little is ever said about its history.

Though experts around the world have spent a lot of effort in trying to dissect the aesthetical dynamics of this art-form; and on how these dynamics are a reflection of a process which sees Pakistan’s traditional folk imageries become fused with those of modernity, which the drivers come across on the roads, very few have attempted to trace the history of this forthright, yet enigmatic, art-form.

Though experts around the world have spent a lot of effort in trying to dissect the aesthetical dynamics of this art-form; and on how these dynamics are a reflection of a process which sees Pakistan’s traditional folk imageries become fused with those of modernity, which the drivers come across on the roads, very few have attempted to trace the history of this forthright, yet enigmatic, art-form.

A much restrained version of this art-form was present in the subcontinent in the 1940s.

It first appeared on trucks and lorries driven by Sikh transporters who would paint a portrait of their spiritual Gurus, or those who helped form the Sikh religion.

The portraits were painted with the loudest of colours. Simultaneously, Muslim transporters and drivers began to paint portraits of famous Sufi saints on their trucks and lorries.

By 1947 — the year Pakistan emerged as an independent country — truckers began to add more elements around the portraits of the Sufis, such as whole landscapes, flying horses, peacocks, etc.

In the 1960s, a strand of truck art in Pakistan began to incorporate politics.

Heavily painted portraits of Pakistan’s first military dictator, Ayub Khan, began to emerge on trucks which were mostly owned by transporters from Khan’s home province, the NWFP (present-day Khyber Pakhtunkhwa).

Ayub’s regime was largely secular-nationalist in disposition and his state-backed capitalist policies had triggered rapid industrialisation in the major cities of Pakistan.

Though the transporters too, had benefitted from these policies, their homage to him (on their trucks), had more to do with the fact that he belonged to their province and had encouraged the migration of labour from NWFP to the booming metropolis, Karachi.

In the early 1970s a most interesting phenomenon galvanised the genre of truck art.

Till the late 1960s, trucks were mostly being painted with spiritual and exotic images on the rear of the vehicles.

From the early 1970s, images and calligraphy began to completely engulf the whole body of the vehicle.

This was prompted by the manner in which billboards and hoardings of Pakistani films became louder and more kaleidoscopic in appearance.

In turn, those painting such billboards were inspired by the ‘psychedelic art’ and Pop Art which had begun to mushroom in the west from the late 1960s onward.

So the painters of truck art, mostly stationed in workshops and cheap roadside eateries along Pakistan’s highways, began to incorporate the complex and loud wall-to-wall style adopted by the billboard painters and fused it with the already established flair of the truck art genre.

The first to get painted in this manner were the ‘mini-buses’ of Karachi. A 1975 feature (in the now defunct Urdu newspaper, Aman), quotes a mini-bus driver describing his heavily decorated and painted vehicle as a dhulan (bride). The style was soon adapted on trucks.

In Paradise — a book about the famous but now defunct ‘hippie trail’ which ran from Turkey to Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan and all the way to India and Nepal — mentions how a group of European hippies (in 1974) would take LSD and then go bus and truck spotting on the roads of Pakistan! To them it was ‘psychedelic heaven.’

The sudden burst of ceaseless colour and imagery on trucks and buses in the 1970s also had to do with the extroverted nature of the Pakistani society during the populist ZA Bhutto regime (1971-77).

What’s more, Bhutto became the second political figure to begin appearing on trucks — mostly on lorries owned by transporters from the Punjab and interior of the Sindh province.

By the 1970s, non-Pakistani figures also began to appear in truck art. For example, martial arts expert and film star, Bruce Lee, became hugely popular in Pakistan.

He became the first non-Pakistani celebrity to appear on trucks, surrounded by the traditional imagery of truck art, thus creating a most surreal effect.

With the kind of impetus which it had enjoyed in the 1970s, truck art became a lot more complex, elaborate and ubiquitous in the 1980s.

In fact, it also produced its first ever super-star. His name was Kafeel Bhai Ghotki.

Ghotki Taluka is a dusty town in the northern most districts of the Sindh province. The majority of the people settled here are indigenous Sindhis, but the town also boasts of having a sizeable Mohajir (Urdu-speakers), Baloch, Pakhtun and Punjabi settler population.

Just like the overall Ghotki District, Ghotki Taluka too, is largely an industrial town, known for having a number of manufacturing and production plants and factories.

However, in the early and mid-1980s, Ghotki became famous for something that had absolutely nothing to do with factories.

Many Pakistanis began noticing the following text signed behind colourfully painted and decorated trucks and lorries: ‘Kafeel Bhai Ghotki Wally — Right Arm Left Arm Spin Bowler’.

The frequency with which these words began to appear on trucks and lorries on the roads of Pakistan was such that many motorists became curious enough to actually stop and ask truck drivers, who on earth this Kafeel Bhai was (and what the heck was a right arm left arm spin bowler)?

The funny thing is that (initially) many drivers when asked didn’t even know that the mentioned text had been placed at the bottom of the multi-colored images and pictures painted behind their trucks.

When some regional Sindhi newspapers investigated the phenomenon, they discovered that Kafeel Bhai was a young cricket enthusiast and a gifted painter who came from a humble, working-class background in Ghotki.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, he had fancied himself to be the only bowler in the world who was able to bowl devastating off-spin with his right arm and an equally devastating leg-spin with his left.

He did manage to get a place in a few club sides in Ghotki where he tried to prove his uniqueness on the city’s grubby cricket grounds. Though he actually could bowl from both his arms, the ball would hardly ever turn and he was usually taken to the cleaners by the batsmen.

Blaming his fate as a bowler on the flat pitches of Ghotki, he decided to try his luck on the cricket grounds of Sindh’s sprawling and cosmopolitan capital, Karachi.

In Karachi, he couldn’t even bag a place in a modest club side and he returned to Ghotki heartbroken and convinced that the Pakistan Cricket Board couldn’t understand his unique cricketing abilities.

In Ghotki, Kafeel Bhai began to spend his time hanging out at the small tea stalls and eateries near the petrol stations on the highway that ran past Ghotki.

These stalls and eateries were mostly frequented by truck drivers who were driving their trucks to and from Karachi (in the south) all the way to Peshawar (in the north), carrying industrial goods, wheat, sugarcane, etc.

Though many of these trucks had all kinds of images painted on them, Kafeel Bhai began to spot trucks that didn’t, and offered to paint them. He only asked the drivers to pay for the paints and brushes required for the job.

The drivers loved his work that mostly included painted images of flying falcons, famous Pakistani vocalist, Madam Noor Jehan, horses, and Lady Diana (!); but what they didn’t know was that Kafeel Bhai was signing off his work as ‘Kafeel Bhai Ghotki Wallay – right arm left arm spin bowler’.

Even when (in 1987) some mainstream Urdu weeklies in Karachi began running a feature or two on Kafeel Bhai, and truck, van and lorry drivers now insisted that he put his name/signature line on their vehicles, Kafeel Bhai refused to accept any money for his work. Instead, he’d just ask for some paint, brushes and maybe a cup of tea at one of the tea stalls where he would spend his days and evenings.

By then Kafeel Bhai had already expanded his signature line that now read: ‘Mashoor-e-zamana spin bowler, Kafeel Bhai koh salam’ (Greetings to the world famous spin bowler, Kafeel Bhai).

But what did he do for a living? Nothing. His lunch and dinners were usually paid for by the truck and lorry drivers.

Kafeel Bhai’s ‘fame’ reached a peak in 1992 when a French art magazine published some pictures of his truck art.

A group of French men and women also came to Ghotki for a visit. They offered to take Kafeel Bhai to France where they wanted him to paint over some trucks and public buses in Paris.

Kafeel Bhai agreed, but only on one condition: He will be allowed to put his signature lines(s) on every French truck and bus that he would paint.

His French patrons responded that this they could not guarantee this but he would be paid well. Hearing this, Kafeel Bhai turned down the offer!

Kafeel Bhai had now entered his mid-30s and one fine day simply stopped painting.

After borrowing some money from one of his many fans, he set up a small furniture shop. After the shop began to turn up a small profit, he finally decided to get married.

Then, in the early 2000s, he suddenly sold his shop, packed his bags and moved to Karachi with his wife.

Nobody is quite sure where in Karachi he lives or what he does for a living. Kafeel Bahi just decided to vanish and so did his images and signature lines on trucks.

It may not look it, but truck art has continued to evolve — now more than ever. It continues to incorporate and fuse modern aesthetic elements and imagery with traditional spiritual and folk ones.

Sufi saints, spiritual vagabonds, the flying horse, the eagle, the peacock, the falcon and imagined scenes of paradise (jannat) are painted side-by-side popular political figures, military heroes, famous cricketers, show-biz personalities, F-16 jets and missiles.