Flight Attendant Uniforms: Look Through History

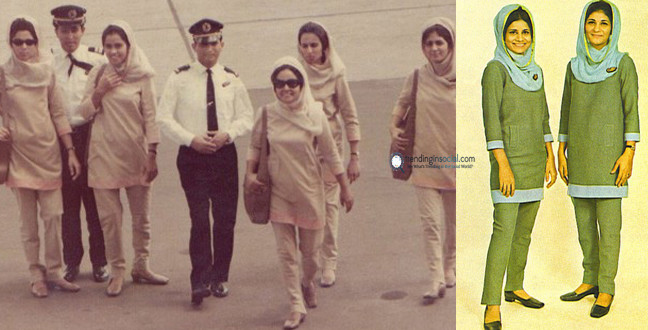

For more than 85 years, the safety and service professional — variably called stewardess, hostess, and flight attendant — has been dressed in outfits designed to signify a distinct role in the workplace, project the identity of the airline, and reflect the popular fashions of the era.

In the early days of flying, flight attendants were registered nurses ready to assist in case of on-board illness or plane crashes (both much more common back then), and were also subject to strict parameters for their physical appearances. In order to be considered for the job, a woman would need to be between 5’ and 5’9” tall and under 135 pounds in proportion to her height. Glasses were often not permitted. There were also strict rules about makeup and hairstyles, as well as rules against having a “broad nose,” a requirement that, according to Gloria Steinem, was “only one of many racist reasons why stewardesses were overwhelmingly white.” In 1938, TIME reported that “to get their $100-to-$120-a-month jobs, applicants for the 300 stewardess posts [since 1930] had to be pretty, petite, single, graduate nurses, 21 to 26 years old, 100 to 120 lbs.”

While women undoubtedly faced discrimination, some of the restrictions on body type were indeed reflections of the needs of aircraft at the time. What would be seen as a form of body shaming today was based on the realities that the cabin interiors of these early airliners were very small with low ceilings and that weight, in an airplane, translated to fuel, and fuel translated to money . It’s the other restrictions on body type and appearance that raise the eyebrows of students of this history, restrictions that have nothing to do with the safety or efficiency of an aircraft. Alongside rational physical requirements, airlines added “words like ‘attractive’ to the list of requirements along with height and weight restrictions.

Outfits on board also generally had little impact on the functionality of the aircraft or the safety of the passengers (hard to imagine that short skits and high heels were very helpful in times of crisis). Women were required to wear heels at all times unless in the air, when they were permitted to change into flats, as well as girdles so they could appear smooth underneath their skirts, and “perky little hats” as Betty McCann, a stewardess in the fifties, refers to them in a 2011 piece she published on Mass Live about her experience flying in the mid-century.

A registered nurse credential was required at first and the uniform played on the traditional look of that occupation. Militarism was also used in female uniform design to convey authority and induce related behavior. As the post-war era made flying available to a wider range of civilians, there was an influx in commercial travel, making it an attainable luxury for the American middle class. Recreational flying became an extraordinarily competitive industry, and it was in this era that we started to see the sexualized ideal of the “stewardess” used as a marketing tactic.

The stewardess became a distinct new figure in popular culture. This generated a mythos that began to mask the more nitty-gritty realities of the job, which was quite physically demanding and included safety and security aspects. The employees began spending more time in grooming classes and less time in training, and the role became sexualized in increasingly overt ways. Much of this was pure male chauvinism, as promotions and marketing were still aimed at a predominantly male clientele. Some airlines, but not all, took this form of exploitation to absurd levels. An example of such can be found in the striptease ad from Braniff International Airways called Air Strip, advertising the eccentric Emilio Pucci uniforms designed with layers that were meant to be removed throughout the flight. The increase in airline advertising, where the promise of scantily clad young ladies serving men up in the stratosphere was used to lure in passengers on commercial flights, had a direct impact on the sexualization of the stewardess figure.

As part of many burgeoning social movements, flight attendants eventually came forward with hopes to change the discriminatory practices associated with the flight industry. “With challenges to unfair labor practices for female employees, mostly under Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, many of which resulted from long, drawn out lawsuits and effective collective bargaining, there are more protections for modern day flight attendants. Uniforms today certainly reflect a more well-rounded approach to size and age ranges of employees. Also, as restrictions were challenged, such as mandatory retirement, height and weight limits, equal pay, etc. and with an influx of male hires, the uniform began to reflect broader and more practical design sensibilities.

Over the last decade or two, many airlines have adopted more conservative workwear looks for their uniforms—typically in navy blue as a nod to professionalism and the business-class market segment. At the same time, there are airlines that choose to stand out among this backdrop of more conservative looks, tapping designers to create special collections for their uniforms, such as Vivienne Westwood for Virgin Atlantic, Gianfranco Ferré for Korean Air, and Christian Lacroix for Air France.

One thing is certain: while flight attendants are constantly on the move, the importance of what they wear doesn’t seem to be going anywhere.